While devastating for the people who lost their jobs, this kind of story doesn’t attract much attention in 2025. A media outlet announcing layoffs is now as newsworthy as a fish proclaiming that it’s wet.

However, there was an eye-opening justification for the layoffs that is quite telling of the state of the media these days: According to The Information: the outlet’s parent company Axel Springer is:

“[Moving] away from businesses that are reliant on user traffic…. Instead, BI will focus on areas such as live events.”

Live events have been the journalism industry’s favorite set of jangly keys for at least a decade now. From Forbes’ array of conferences for lucrative demographics to the Wall Street Journal’s glorified vacations for executives to the endless proliferation of award shows and live podcasts and fireside chats, it’s now hard to go a week without being invited to an exclusive convening of thought leaders and luminaries (maybe with food trucks, or a meditation room, or a special musical guest).

The logic is straightforward: if lots of regular people won’t pay for a digital subscription, then target a smaller group of professionals whose companies will foot the bill for something more tangible—like a networking experience, with happy hours.

The math works, in theory. Some of those tickets start upwards of $5,000, which equals a lot of $50 subscriptions. And media outlets can sell sponsorships, or team up with corporations to offer special products, or tap one of the other creative money-making opportunities that just don’t exist for a traditional words-and-pictures business.

The only problem is that these media outlets are undermining their own appeal. Nobody goes to Forbes Women for the canapés—they go because Forbes carries a cachet that can only be earned from years of being a trusted industry voice. Appearing in those pages bestows a unique status (or at least used to) because a (supposedly) objective journalist decided you were interesting and important enough to write about, with the actual writing being indispensable as it allows you, years in the future, to point at that story and say: “Look, here’s me in the news.”

There’s nothing wrong with media outlets exploring new revenue streams, and newsrooms are always fluctuating in size. But outlets can only hollow out their core product so much before it collapses entirely, and a growing number of media organizations seem to be reaching that point now.

Once a news company stops making news, how long before it makes itself irrelevant?

Because the last word is rarely the end of the conversation.

Much like penguins, we enjoy bringing you little gifts to show we care:

We’d prefer a world where advice on what to do if you’re targeted by the White Houseisn’t necessary, but since this is the world we have, this piece is worth a read if you work in any industry besides “weapons” or “red hats.”

Speaking of the White House, this cross-Greenland travelogue is a fascinating look at the U.S.’ history of conquest due to deepseated boredom and ennui.

Asian American Futures is hiring a Communications & Development Manager—fully remote, $80-85k a year plus comprehensive benefits (and every other Friday off).

Here’s what one of us is currently reading:

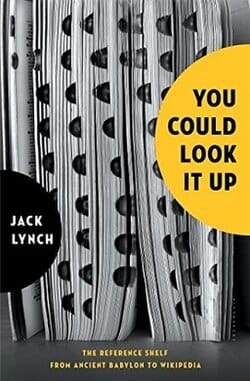

You Could Look It Up: The Reference Shelf From Ancient Babylon to Wikipedia – Jack Lynch

How do people know what they know? In a world of shifting, sliding information, it’s fascinating and surprisingly relevant to look at how people have answered this crucial question for the past few thousand years.

Bonus bit: we all know that algebra was named by a famous math whiz during the Abbasid Caliphate. But did you know that the same dude is the source of the word “algorithm”?

“We can be certain, though, that Muhammed bin Mush Al-Khwarizmi was a polymath. He gave us two words whose importance has only grown in the centuries since he lived: the title of his book Kitab al-muktasar fi hisab al-jabr wal-mugabala, or The Concise Book on Calculation by Restoration and Compensation, is the source of the word algebra (al-jabr means ‘compensation’), and his name, al-Khwarizmi, once Latinized and then passed around through the modern languages, gave us the algorithm. Every high-tech computer calculation pays tribute to the ninth-century Islamic genius.”

Not every organization has to acknowledge "these uncertain times." But if you're going to join that conversation, it's wise to offer people something more than empty therapyspeak.

Guessing about what the future holds is an amusing and low-risk pastime—most of the time, newspapers won’t write stories about you admitting you were wrong—but we still think it’s best to be realistic. We also believe it’s important to have a sense of humor about these things. Because have you seen the world out there? So, having established the parameters of “practical” and “fun,” here are the themes that (we hope) will define communications in 2026:

[The] forces that defined the past year—the AIfication of everything, the Trump Administration’s crusade to reshape the world, the ultra-personalized emptiness of digital life—still seem to have a head of steam. When they’ll run out is anyone’s guess. So here’s a prediction for the new year: people are going to start valuing a human touch a lot more.

If the 2010s were an era of diversity in media, the 2020s are one of consolidation. This presents obvious challenges when trying to get small or medium organizations mentioned in the news. Success depends on riding the waves that already exist, instead of trying to make new ones.

Press releases sometimes feel like relics from a simpler, more innocent time. Much like fax machines, most people are aware they continue to exist. What’s less clear: who actually uses these things in 2025? And for what purpose?

The ability to not sound like you were just lobotomized by a team of nonprofit execs with MBAs has become a way to stand out. It's “riskier” in a sense, because it’s easier for people to tell what you’re actually saying—and potentially criticize it. On the other hand, nobody’s listening to the jargon jockeys anymore.

When we founded this agency last year, we had a pretty straightforward idea of how we’d run our business: do good work with our own hands, communicate honestly, and treat people fairly. We thought this would be the simplest path to earn a decent living and contribute something to human society. After a year of this experiment, here’s what we’ve found...

Working with people you think are interesting is good for your own personal and career growth. If their ideas are good enough to work on for free, someone will eventually pay them for that, and you’ll have forged a professional relationship—or better, a friendship—with someone smart.

There’s nothing wrong with media outlets exploring new revenue streams, and newsrooms are always fluctuating in size. But outlets can only hollow out their core product so much before it collapses entirely, and a growing number of media organizations seem to be reaching that point now. Live events are not going to save them.

Comms agencies that are good at their work tend to be curious and resourceful. We can’t pretend to be ignorant about the people and products we’re telling the public to trust. In all but the rarest cases, the agency knows what it wants to know. Business is never as pure or idealistic as we might want it to be. It does have ethical boundaries, though, and these are especially important at inflection points like the one we’re in now.

We humans like to explore for exploring’s sake. We’re pleased when we find an unexpected beautiful thing, and we feel a sense of satisfaction when we “discover” something that’s not immediately obvious to the casual observer. People want to spend time in environments where these opportunities are available—which is something to consider when building (or updating) your website.

Nonprofits shouldn't have to beg for funding to provide vital services. But with federal funding suddenly scarce—and thousands of organizations scrambling to attract attention from the big donors that remain—a new kind of comms strategy is needed.

The platform doesn't drive traffic to your site. The ads don't convert. And these days most of the "engagement" comes from spam bots or virulent bigots. It's time to move on from Twitter—but to where?

Everybody loves talking about the importance of "storytelling" for building your organization's name recognition. And it really can work—but it requires more planning and effort than firing off the occasional blog post or Instagram post.

If your nonprofit or small business has a clear message to share about a concrete goal it wants to achieve, video can do that better than any other medium—if it's done right.

Today, even a glowing review in the New York Times doesn't move the needle that much. Getting people's attention takes a more creative approach. And it all hinges around owning the means of (content) production.

In the inaugural issue of A Better Way to Say That, we explore important questions like why does this newsletter exist? and why does PSE exist, for that matter? We also share a roundup of exciting new book launches, events, and job postings—along with perhaps the most effective fundraising email ever written. As far as business-y newsletters go, it's a fun read!